Revit Guides

Data Management

ELI5

Operational Team Context of Information Exchange

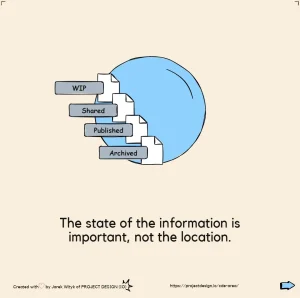

CDE state

Appointed Party context of information exchange

lead appointed party

Delivery Team context of information exchange

Lead Appointed Party context of information exchange

federation strategy

Shared context of information exchange

Appointing Party context of information exchange

Dynamos, Boilers, and the Costly Copper of Edison’s 1882 Pearl Street Station

On September 4, 1882, Thomas Edison’s Pearl Street Station in New York City became the world’s first commercial central power plant. That afternoon, Edison gave the signal for his chief electrician, John W. Lieb, to “close the switch” and energize the grid With a loud thunk, the lights in a multi-block area of Lower Manhattan switched from the flickering amber glow of gas lamps to the steady white radiance of incandescent electric bulbs. It was a historic moment that marked the dawn of the electric age, made possible by an interplay of roaring boilers, humming dynamos, and a web of underground copper wires.

Dynamos: Generating Electricity in 1882

Dynamos (early electric generators) were at the heart of Edison’s Pearl Street power station. Edison’s team installed six massive “Jumbo” dynamos at the station – each weighing about 27 tons and rated around 100 kW (able to power roughly 1,200 incandescent lamps each). These dynamos produced direct current (DC) electricity at about 110 volts for distribution. In essence, the dynamos converted mechanical energy into electrical energy. They were specifically built to maintain a constant voltage (hence called constant-voltage dynamos) suitable for Edison’s new incandescent bulbs. By design, the six generators together could supply up to an estimated 7,200 lamps, though on the first day only about 400 lamps were actually connected, serving 82–85 initial customers in the area.

Boilers and Steam Engines: Powering the Dynamos

If dynamos were the electric heart of the station, boilers were its muscles, providing the driving force. The Pearl Street Station housed four coal-fired steam boilers, which produced the high-pressure steam needed to run reciprocating steam engines Each dynamo was mechanically coupled to a steam engine (manufactured by Armington & Sims) – and those engines got their motive power from the steam supplied by the boilers In practical terms, without the boilers there would be no steam, no engine motion, and thus no electricity The boilers burned coal (shoveled in around the clock by firemen) to boil water into steam, which then drove the pistons of the engines.

The engines in turn spun the dynamos to generate electricity. It was a classic 19th-century power train:

coal → boiler (steam) → steam engine → dynamo → electricity.

To summarise the process, here’s how Pearl Street’s system worked:

Coal-Fired Boilers Produce Steam: Coal combustion in the station’s boilers turned water into high-pressure steam (around 80–100 psi)

Steam Engines Convert Steam to Motion: The steam was piped into reciprocating steam engines, forcing their pistons to move. This provided mechanical rotational energy.

Dynamos Convert Motion to Electricity: The steam engines were directly connected to the dynamos’ shafts. As the engines turned, the dynamos generated DC electricity at about 110 V.

Power Distribution to Customers: The electricity flowed out through thick copper conductors in an underground network, delivering power to lamps in homes and businesses across the service district.

Both the dynamos and the boilers (with their steam engines) were critical technical components of Edison’s system – each played a different role in making electricity available. Dynamos generated the electricity, but only because boilers and engines provided the mechanical power to run those generators. In the Pearl Street Station’s design, all these pieces worked in unison; as one contemporary description poetically put it, “every component of the Pearl Street Station – from the roaring boilers to the humming dynamos – worked in harmony” to create the first practical electric lighting network

The Buried Copper: Edison’s Costly Underground Wiring

The statement that “the buried copper nearly cost more than the boilers, dynamos, real estate and lamps combined.”

This is not an exaggeration – in fact, Edison’s underground copper wiring network was the single most expensive part of the entire Pearl Street project To distribute power to customers over several city blocks, Edison had to run an extensive system of conductors beneath Manhattan’s streets. Approximately 80,000 feet (over 15 miles!) of copper conductors were installed in conduits and manholes under the paving These were thick, insulated copper cables, divided into two parallel “half-round” copper wires per line, encased in jute and special insulation (a mix of beeswax, linseed oil, and asphaltum) to prevent shorting out At a time when copper was an expensive commodity, the sheer quantity needed for Edison’s low-voltage DC grid made the wiring infrastructure astonishingly costly.

Contemporary accounts and engineering analyses confirm that the network of conductors (feeders and mains) was the most expensive component of the Pearl Street Station project.

In other words, Edison ended up spending more on copper wire and distribution hardware than on any other single element of the system – likely nearly as much as all the generators, boilers, building, and lamps put together. This high cost of copper nearly derailed the economics of the venture. Edison’s team quickly responded with an innovation: they moved from a 110 V two-wire system to a 220 V three-wire system, which cleverly allowed the same power to be delivered with far less copper wire. By using a three-wire DC circuit (with two “hot” conductors at +110 V and –110 V and a neutral return), they could halve the copper needed for a given amount of power, since loads could be balanced between the two halves of the circuit.

This change “greatly reduced the amount of copper needed” and yielded a significant cost saving for the station.

In short, the buried copper wires were indeed a killer line-item in Edison’s project budget – so much so that it spurred a technical change in the system to bring costs down.

TL:DR

In summary, Edison’s Pearl Street Station achieved its spectacular debut of electric lighting through a combination of dynamos and boilers (among other hardware). The dynamos were the electric generators that produced the power, and they were driven by steam engines which derived their energy from coal-fired boilers – a quintessential steam-powered system.

All these elements were essential, meanwhile, the oft-overlooked star (or villain) of the show was the vast copper wiring network beneath the streets, which turned out to be the costliest part of building the first electric grid.

When John W. Lieb closed that switch on 4 September 1882, it lit up a portion of downtown Manhattan with Edison’s new electric light – and behind that moment were boilers belching steam, dynamos spinning electricity, and extremely expensive copper cables knitting the system together.

Cover image source: The New York Historical, accessed 07/06/2025.